Magical Thinking

Yavuz Gallery - Sydney

August 3 - 26

69 Reservoir St

Surry Hills NSW 2010

Human life on Earth, depending on who you ask, is a story of journeying from water to land. From microcellular life to fish like animals seeking the land, from handmade rafts guided by gods and stars to land, empires violently expanding via fleets across the seas, loading up boats with enslaved people in the name of empire and capital, braving rough seas in pursuit of land that may welcome.

Before there was life on Earth, there have always been rocks. The oldest known rocks are 4 billion years old. The country I live on has some of the world’s youngest known aged 300 million years old.

Where science and geology might provide the material context, though imprecise due to human fallibility, provide material context, language provides a cultural insight. Here I turn to metaphor to understand Western relationships with rocks. In the Anglophone world, rock and stone find themselves employed to mean varied things. A cornerstone, keystone or bedrock is to be a staple and vital to something. To be someones’ rock is to be reliable; an immoveable constant. I have enjoyed the constant of a rock, particular rocks along long hikes provide a milestone (another metaphor!) and a place to rest. More than once I have thrown my body along to take a well-earned break. Particular rocks tells me I am close to home or I am on my country.

A rocky road tells us a journey has been challenging. Drawing blood from a stone is to try and pry the impossible from a person. To be stony-faced is to be unfeeling. Is this true though? An inability to read the surface doesn’t mean there is nothing below the surface. Between a rock and a half presents an impossible bind. Stone-cold similarly relies on an unreliable narrator (the observer). To be of the ‘stone-age’ is deployed by racists to describe Indigenous peoples, once again revealing an inadequacy in the narrator rather than that being described.

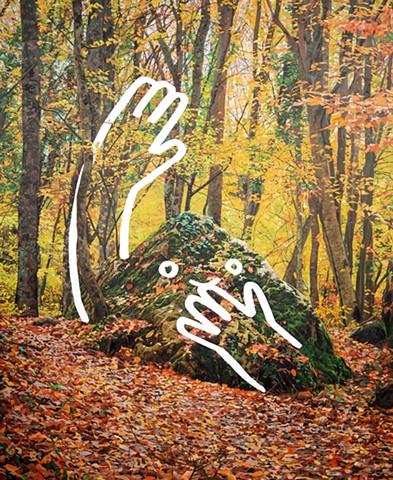

After an oeuvre set amongst the ocean, journeying the waters, anxious self-portraits playfully strewn on rocks, we meet Abdul Abdullah on land. Surrounded by lush, overflowing forest instead of anxious faces, this time they are optimistic. Still cheeky, what do these faces know that we don’t?

These faces stand in as metaphor for the Abdul self. Rocks have been treated by language as immoveable, imperceptible and hard. A history of human life on Earth can also be seen as a history of testing the limitations of rocks. Western progress has been categorised by our ability to destroy, extract, rocks malleable and conquer. Western civilisation has blown them up or broken them apart to change the course of a river, to pave cities and mined them in the name of progress.

Abdul’s happy faces are an invitation to think beyond metaphor. Our metaphors have not yet accounted for the human toll on rocks. We imagine ourselves as the victim of rocks and imagine them as objects to conquer. Human imagination can cage both the metaphor and material. Rocks are neither unmoving or impervious. It is difficult to imagine but these hard seemingly impenetrable rocks are vulnerable too. And if these ancient rocks are vulnerable then all of us are too.

- Nayuka Gorrie, 2023